This is a slightly revised version of a short article I first published on my personal blog in September 2020. I share a quick review of some of my reading in July after the article.

Some people do not like to read, but that is usually not their fault. They have never been taught how to read or given the permission to discover what they will love to read. I was fortunate to grow up in a reading household and to have considerable liberty in my reading selections—maybe too much, at times. I did not ask my parents if I could read a book. I simply found one on the shelf that looked interesting and plunged in. I didn’t enjoy school very much, but I loved the school library. The yearly visit of the Scholastic Book Fair was almost as good, and sometimes better, than Christmas, and when my elementary school class was not very interesting I found that I could hide an interesting book inside my textbook, at least, until the kid sitting behind me ratted me out. (I probably learned the book inside a book trick from reading about it in a book.)

Everyone should enjoy reading because reading is one of the most important ways to grow as a human being. If you do not enjoy the discipline, you will not continue doing it for very long. That does not mean you should enjoy reading anything. Some of us have very eclectic tastes and can be happily occupied with many different types of literature. But just as every one should have a job at some point in their lives that is so unpleasant it clarifies for them the reasons they want to work hard so as not to end up in that kind of career, so everyone should read some books that help them learn what a good book is not and why we ought to be willing to work hard to find the good ones to read and enjoy.

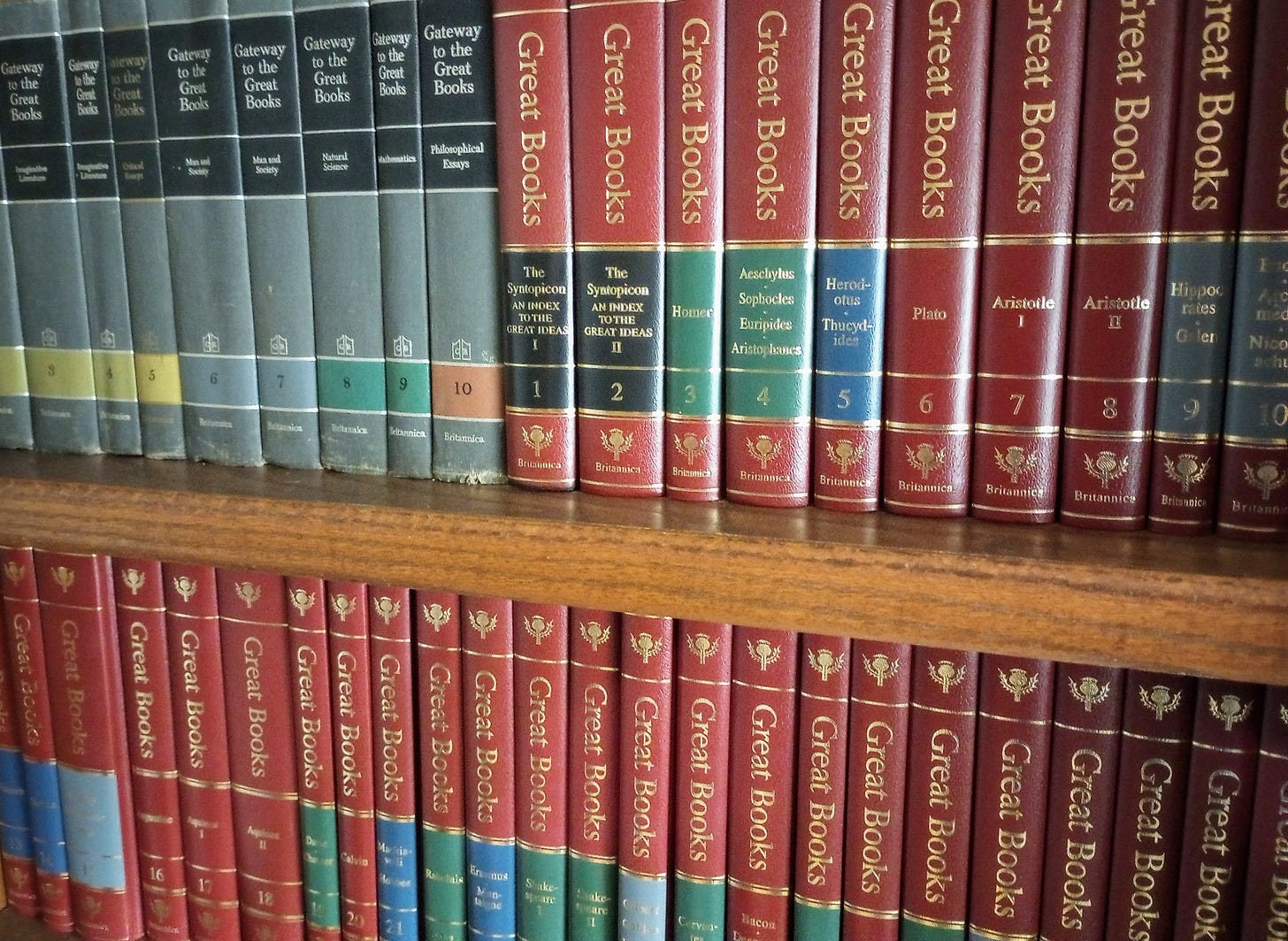

People approach reading in different ways. I remember hearing an interview with John MacArthur several years ago in which he expressed astonishment that anyone would ever want to re-read a book. I was astonished by his astonishment. Have you really enjoyed a book you never want to read again? I might understand if the first taste was so perfect the reader would not dare to return to it because of the certainty of disappointment. But my own philosophy of reading was shaped largely by C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Mortimer Adler, so my reading life is largely a search for those “great books” that I plan to re-read for the rest of my life. A considerable percentage of my yearly reading is devoted to re-reading books I have read before, and there is a list of books I re-read every year. I don’t consider a book very valuable if I will only profit from reading it once, and there are many books you must read once to discover they were not worth reading at all. But that being said, we cannot afford to be too picky if we enjoy reading and read widely. Some reading should simply be mind candy, the kind of book whose only profit is the entertainment that it brings. Oreos can be enjoyed—and are always best enjoyed dipped in a cup of coffee—but they should not be eaten too frequently or in great proportion compared to the rest of one’s diet. The same is true of the kind of reading that passes the time but does not speak to the soul.

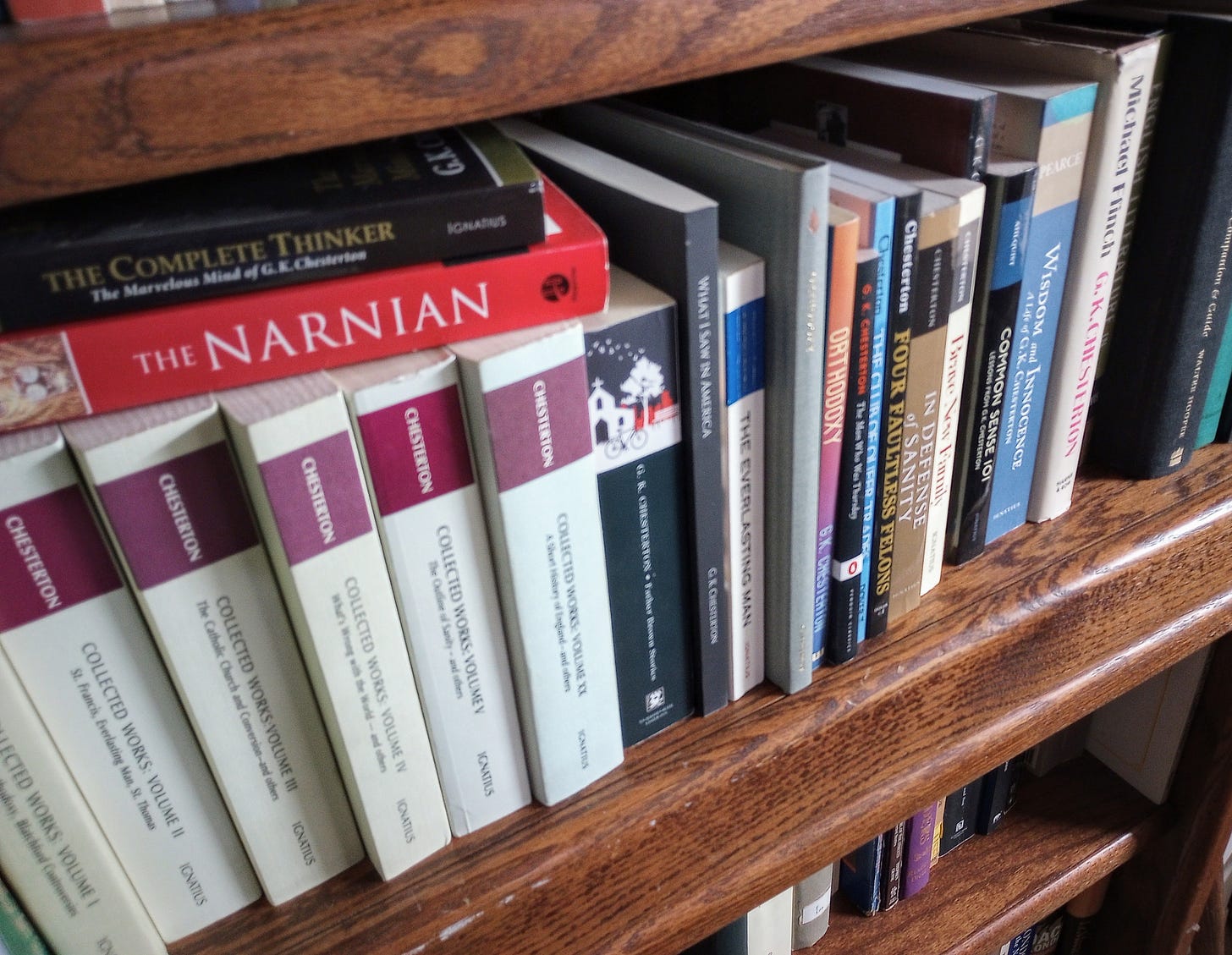

Great books are our teachers, and good books are our companions. Poor books are obstacles we meet along the way. If you are a Christian, there is one book you will love, even if you do not love any other. That, of course, is the Bible. But if you know the value of reading, there will be many others you also find profitable. Books contain the wisdom of the ages, and its foolishness. They allow us to participate in conversations with those wiser than we are and to discover that neither publication nor the passage of time can make a poor thinker or bad writer (which are actually the same thing) into a good one. We dare not trust our own wisdom or the very limited pool of people each of us knows. We love our friends and associates, but not many of them are writing books or emails or Facegram posts that will be read one hundred years from now, much less a thousand. No matter how wise and good-natured you may be, you probably do not want me calling to chat at three o’clock in the morning, but Chesterton never seems to mind when I do so.

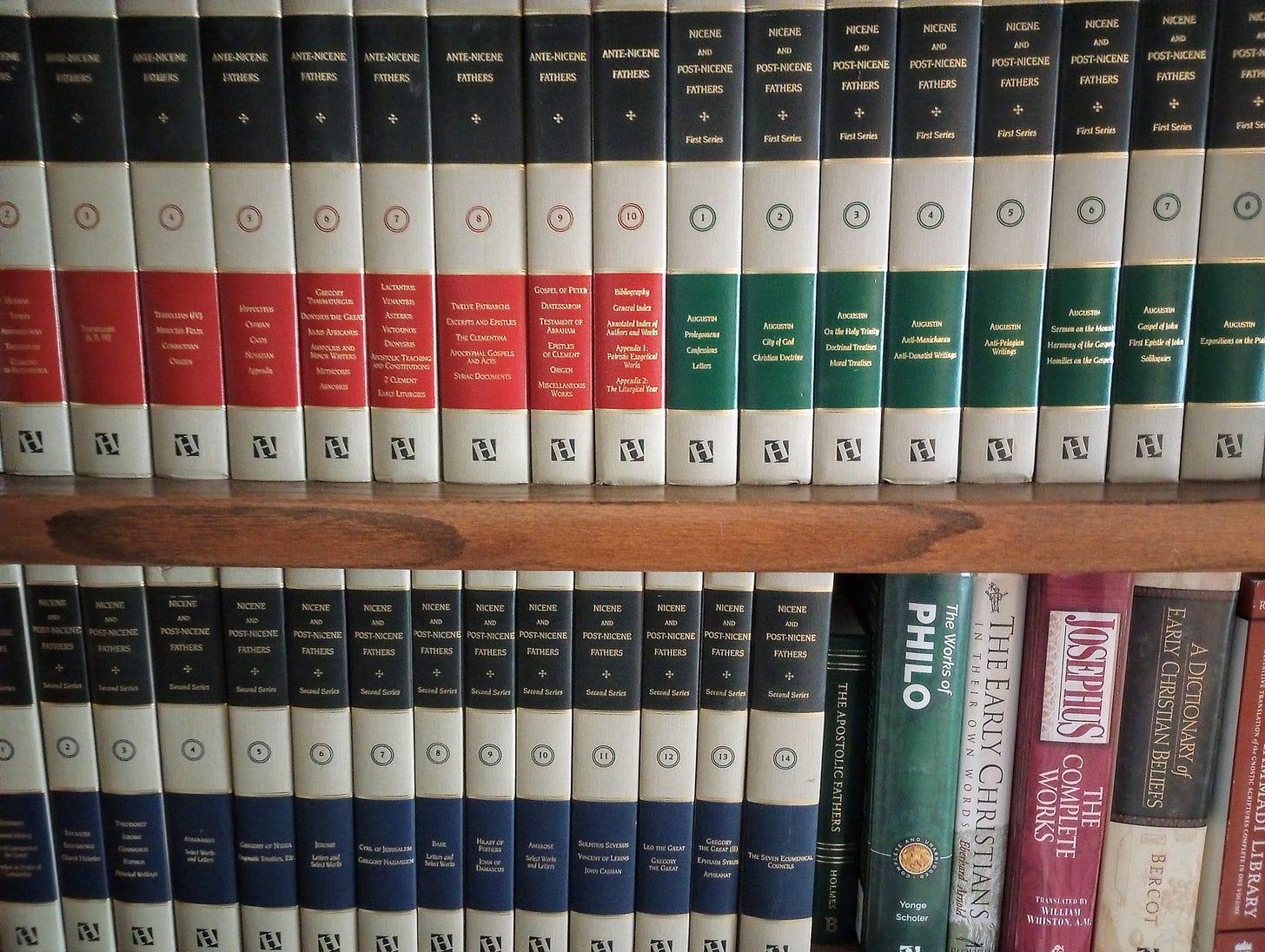

Life is too short to read everything, and most of what has been written is not worth reading anyway. One must be selective. If you care to depress yourself, you can easily calculate roughly how many books you have left to read in whatever is left of your lifetime. We do not want to waste too many of those, so I prefer to continue conversing with the authors I know will not disappoint me and the works that still have much to teach me no matter how many times I have read them. We should never grow tired of visiting Narnia or trudging through Middle Earth on the way to Mordor. We need to be regularly reminded not merely of Christian and Christiana’s story, but that their story is our story, and that other saints have walked the path our feet are following today. We have much still to learn in the school of Calvin and the Puritans and Bavinck and Schaeffer. There are more questions to ask Aristotle and Plato, and we need to hear more stories about the history of God’s providence in the events of this world. We can do all of this simply by picking up a book and reading it well.

We are not reading for entertainment, though we should find it entertaining. We read because we are incomplete, ignorant, and cold-hearted, and it is the stories and truths we find in great books (and some good ones) that teach, shape, equip, and sustain us. They are instruments in the Redeemer’s hand. I do not spend so much of my life reading books because I enjoy it, I enjoy so much of my life because I spend it reading.

I mentioned in my Friday Review last week that my reading volume (at least, of completed books) is way down compared to the last ten years, though I do expect a significant push in the last five months of 2024 and have already changed some patterns to facilitate it. I tend to be a little too motivated by or focused on stats, so it is important to remember if you log your reading that you are not reading to inflate your ego or impress others. Quite the opposite. We should read because we recognize ourselves to be ignorant. Reading literature should be an act of humility, not a personal accomplishment in which to boast.

Here is a quick review of some of the titles I read during the month of July.

I have not quite finished Jeremy Carl’s The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism is Tearing America Apart, but I should do so by the weekend. It was recommended by several men I admire, and I heard Carl interviewed on a couple of podcasts before getting the book and beginning to read. It is a substantive and carefully substantiated look at the way in which anti-white policies, promoted in the name of correcting historic wrongs and persistent disparities, have become pervasive, intrusive, and undeniably destructive to American society. Carl is very careful in his prose, not inflammatory, provocative, or emotional. He writes with the dispassion of an academic who has studied his topic carefully and seeks only to expose the reality and highlight the inherent injustice. There is structural racism in American society today, but it is not in the form that is commonly asserted and accepted.

Russell Kirk’s Concise Guide to Conservatism is a brief (~100 pages) collection of essays explaining the “conservative” perspective on a variety of social topics. The chapters include: The Essence of Conservatism, Conservatives and Religious Faith, Conservatives and Individuality, Conservatives and the Family, Conservatives and Just Government, Conservatives and Private Property, Conservatives and Education, and several others. The collection was originally published in 1957 as The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Conservatism, “a gentle gibe at George Bernard Shaw’s Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism” (from the Introduction by Wilfred M. McClay, xii). The edition I read was republished in 2019, after the ascendance of Donald Trump and a couple of years into his administration. The content was useful, weak in some places, unaware of more recent developments and divisions within the conservative camp, but overall a worthwhile introduction to fundamental perspectives shared by conservatives on a variety of topics. Some of the chapters were better than others, and the work as a whole displays the liabilities and inevitable downfall of conservatism separated Christian and biblical convictions. There are other books that may do the work of introducing conservatism more effectively, though one should ask what we are seeking to conserve before committing to life as a conservative regardless of one’s historical, political, and social context. But Kirk is a thoughtful writer, and this collection has its uses. I usually do not review volumes I do not recommend, but I do not not recommend this one, and since I have many friends who are fans of Russell Kirk, it seemed prudent to acknowledge it.

Peter Leithart’s Baptism: A Guide to Life from Death in the Lexham Press Christian Essentials series is, quite simply, the best and most profound book on the sacrament of initiation I have ever read, and I have read a lot of books on baptism, including others by Dr. Leithart. I was astonished to find blurbs inside the cover from both paedo- and credo- baptists, but when I read the book, I immediately understood why. This is not a treatise on the proper subjects, timing, or mode of baptism. It is an extended meditation on the biblical theology, ritual, and symbolism associated with baptism. The Presbyterians to whom I have recommended the volume have been quick to point out the obvious “2CV” (i.e. “2nd Commandment Violation”) in the historic artwork used in the cover and layout of this series. If that is the primary thing that stands out to you, you are missing something profound in the delightfully rich prose printed on the pages. Dr. Leithart is at his best discussing the biblical-theological and typological aspects of sacramentology, and this is a masterpiece in an already large and ever-growing corpus of literature from his pen that will continue to challenge, provoke, and inspire believers and theologians (there sometimes being a considerable difference between the two) for generations to come.

Uri Brito’s The War of the Priesthood expounds the armor of God described in Ephesians 6:10-18 in terms of the Old Testament background as a reference to the priestly garment God’s people are dressed in to engage in spiritual warfare. It is an excellent little volume with Pastor Brito’s characteristically substantive but succinct and easy to read prose. A quick read, this is one to return to periodically for encouragement, meditation, and conversation around the family room or in a small group.

My diet of fiction in the month of July consisted entirely of Tolkien, Twain, and a few chapters of Lewis at the very end of the month, none of whom ever disappoint.

Great read. As a pastor I find that I must hold onto my reading times since it could easily fade away. I also try to add fiction and poetry in my reading.

Thank you Joel for this encouragement. I will pass this article on to the men of my church as we look to restart our men’s book club this fall. I have Uri’s book that you mentioned and look forward to reading it. I also just ordered Leithart’s book on baptism that you mentioned. I am becoming a big fan of his writing.